Two shows at the State Historical Society of Missouri offer a journey into the minds and aesthetics of a Missouri editorial cartoonist and a famous artist of North American wildlife.

Tom Engelhardt

Many editorial cartoonists go for the cheap laugh. But not Tom Engelhardt, retired longtime cartoonist at the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, whose selected works are on display through Oct. 17 in the Corridor Gallery of the State Historical Society in Ellis Library.

“Editorial cartooning when it is produced in the way it was intended, can have a powerful, positive effect on our society and the world,” writes Engelhardt in the Preface to a collection of his cartoons edited by society Curator Joan Stack. The book, titled “Four Turbulent Decades: A Cartoon History of America, 1962–2001, From the Pen of Tom Engelhardt” (The State Historical Society of Missouri, 181 pages, 2015), is a companion volume to the show and for sale on the society’s website.

The show’s dozens of cartoons represent most of the works discussed in the book, spanning from the 1960s to 2001, including one addressing the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks. The framed cartoons enable viewers to fully appreciate Engelhardt’s underappreciated drawing skills.

Engelhardt’s works don’t try for easy laughs or facile social and political commentary. As Stack writes in her Foreword to the book, “He understood that a meaningful cartoon engaged spectators in a dialogue of thought. The dialogue might be inspiring or contentious, but as long as it existed, the cartoon was a success.”

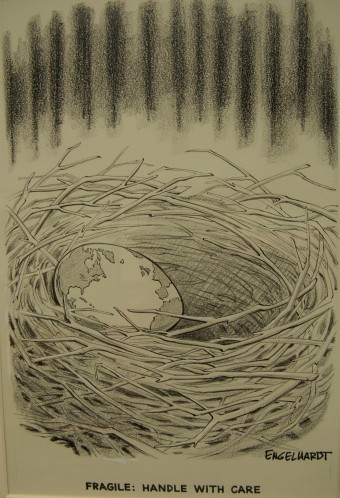

The show includes a 1971 cartoon representing the earth as an egg in a bird’s nest. The caption reads, “Fragile: Handle with Care.” Though Engelhardt was referencing the contemporary awareness of the earth’s environmental limits, the cartoon perhaps speaks more loudly today as scientific evidence mounts on global warming and the limits of the planet’s resources.

Another rendering shows the Confederate flag with a skull in the upper red field, published in 1962. Engelhardt was reacting to the deaths of two African-Americans during a segregation protest in Mississippi that fall.

It is not hard to imagine a similar cartoon published today in reaction to the June 17, 2015, killings of nine African-Americans in a South Carolina church by a purported 21-year-old white supremacist. The subsequent debate over the Confederate flag resulted in its removal from South Carolina’s capital grounds on July 10.

John James Audubon

John James Audubon (1785–1851) is known for his contributions to natural history through his studies of North American birds and other animals. He spent time observing wildlife in the woods and riparian habitats of Missouri, and for a while he co-owned a mercantile business in Ste. Genevieve, Missouri.

Over the course of his career, he identified 25 new species. His field notes contributed to a better understanding of wildlife.

Audubon is best known for his illustrated books The Birds of America (1827–1838) and The Viviparous Quadrupeds of North America (1845–1848). In the Main Gallery are 22 lithographs and engravings for the show “Audubon’s Paper Menageries: Birds and Quadrupeds,” running through Nov. 28. Wall-text offers background on Audubon and explains the complex method used in his hand-colored prints.

Among the works is a life-size picture of two passenger pigeons, a species that was extinct by the early 20th century.

Several illustrations show Audubon’s skills in representing quadrupeds, such as bears, skunks and beavers. Unlike the renderings of birds, these works sometimes show animals reacting to the viewer, as though the spectator has interrupted animal life. It is as though Audubon is underscoring the barrier between humans and wildlife. In “Common American Skunk, 1845,” a female skunk bears her teeth and raises her tail as she glares at the viewer.

Though Audubon is mostly known as a naturalist and wildlife illustrator, the show helps viewers also see him as an artist.