In a rare moment of freedom, three novice monks play along the terraces at the Hsinbyume Pagoda in Mingun, Myanmar.

When Steve Wallace bought his first camera, a 35 mm Pentax MX, he wasn’t dreaming of an armed village in Ethiopia’s Omo Valley, a young woman guarding the tribe’s flowering sorghum fields with a slingshot, scattering hungry birds beneath an ashen sky. He wasn’t imagining a Chinese fisherman casting a net from a bamboo raft, two black cormorants waiting by his side, an eerie fog hanging above the Li River and shrouding the karst mountains — like stubby fingers bursting through a grave — behind them. He wasn’t picturing a barefoot Indonesian shaman wrapped in a purple shawl, face lit by his bamboo torch, the Bromo volcano of Java island belching smoke in the sunset, the whole stunning panorama awash in a purple haze.

In Ethiopia’s Omo Valley, near the Kenyan border, a young woman from the Hamer Tribe shoos birds from the tribe’s sorghum crops with a slingshot.

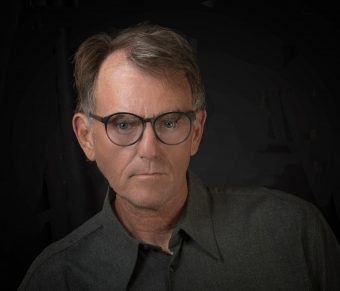

No, Wallace, then a pharmacist and first-year medical student at the University of Missouri, thought maybe his dog would do just fine. Maybe a tree in the backyard. “Nothing in particular,” he says. But within two months, he was converting his spare bedroom into a darkroom, processing his own film. And go figure: When he entered a local contest — submitting a silhouette of a praying mantis — he won. The Missouri native who graduated top of his class at University of Missouri-Kansas City pharmacy school, who was now flourishing in medical school and who would later earn a law degree, too, just to better the hospital attorneys, was also a natural photographer.

“He’s a craftsman, not just a guy snapping pictures,” says Scott Kelby, president and CEO of KelbyOne, an online educational community for photographers. “You take a great composition, add interesting subjects, in a fascinating place, with great color — there’s Steve’s shot. It all comes together.”

With Mount Bromo — an active volcano — smoldering in the distance, a local shaman in Java, Indonesia, hikes to a prayer site at sunrise.

After a prosperous career in both medicine and law, Wallace — now technically retired — travels the globe with a camera in his hand: Myanmar, Italy, Peru, Egypt, India, Vietnam, Ethiopia, Indonesia and more — way more. He captures moments of intense joy and sorrow, of pain and contemplation. Portraits of life in every shade. He pays his own way, hires a local fixer, offers his work pro bono to various nongovernmental organizations, from Asia Partners to Saving Moses and others. And go figure: It’s good — very good. His work has been chosen for book covers and traveling exhibitions, magazines and donor campaigns, and in 2018, Smithsonian Magazine named him a finalist in its 16th annual photo contest, chosen from more than 48,000 entries.

“I think all this is primarily to maintain my sanity in retirement,” he says, eschewing the spotlight. “I’ve always had a nagging feeling I should be doing something productive.”

Raised in Belton, Missouri, Wallace hadn’t always been the scholar he would later become. As a kid, he was far less interested in school than most anything else, especially his grandfather’s farm in Kansas, where he often spent his summers reveling in the outdoors, helping feed cattle and bail hay. But all that changed after enrolling at Metropolitan Community College–Longview in Lee’s Summit, Missouri, after high school. Suddenly, he was earning straight As, and just a year later, he found himself enrolled in pharmacy school in Kansas City. He graduated in 1975 with the same flying colors he would capture, decades later, on camera.

“When I got to college, suddenly everything became fascinating,” he wrote in an email from Ethiopia. “Learning botany, zoology and others seemed to open up a new world.”

After practicing for a year at a small pharmacy back in his hometown, he returned to academia, an atmosphere he’d grown to revere. “If I could be any place in the world, I would be on a college campus,” he says. “I just feel a sense of peacefulness. You can feel the learning that’s going on.” By 1990, he’d stacked his resume so tall it would need FAA clearance: a medical doctorate from Mizzou, a residency in anesthesiology at the Maricopa Medical Center in Phoenix, several years of private practice at the Yuma Regional Medical Center in Yuma, Arizona (where he was elected president of the medical staff), and a pain management fellowship at Massachusetts General Hospital-Harvard Medical School. After exposing financial corruption at the hospital in Yuma, he decided to pursue a law degree, too, “just to stick it up their ass.”

“I interacted with lawyers a lot, and I found that lawyers’ opinions — just by the fact that they’re called a lawyer — were worth more than mine. And at times I disagreed with them. I didn’t understand why their advice was taken and mine was not.”

He earned his law degree from the University of San Diego, still practicing medicine all the while, and passed the California Bar exam in 2002. For the next 10 years, he split his time between Yuma and San Diego, where he’d joined a small legal firm focused on medical malpractice. The years passed in a flash. Every now and then he’d pick up the camera, tinker a little. He bought his first digital in 1994, “essentially a hard drive with a moderately priced Nikon sitting on top of it,” he says, but juggling two jobs in two cities left him little time for hobbies.

“I put it down for a few years, but I’d always pick it back up,” he says. “It’s always been my avocation of choice.”

Although Wallace still practices law part time, he retired from medicine in 2012. And over the years, as he’s gradually stepped away from a life of clients and patients, he’s entered a new one of subjects and spaces. As a self-taught photographer, he’s continually evolving.

“When I first started taking pictures, I looked at the subject, and I tried to get something interesting as far as the subject goes,” he says, “Then I started becoming more sophisticated and made certain my background was good. Now I’m coming to the point where not only the subject and the background are important, but the light hitting the subject has become the most important thing to me.”

Steal even a cursory glance at Wallace’s portfolio and you’ll grasp immediately what he means. Light spills across foreign waters, punches through clouds, filters through billowing linen, saturates horizons and glows at the tip of a fat hand-rolled cigar. In one especially striking photo, taken at the Bagan Archaeological Zone in Myanmar, a young monk sits cross-legged on the floor of a Buddhist temple, reading from a book illuminated by the latticed window behind him. The sunlight pours perfectly through every square, softened by the cheap, smoky incense Wallace lit before the shoot.

“Nothing makes me happier,” he says, “than a hut in the middle of nowhere with one opening to light and that light bouncing off a dirt floor and hitting the subject.”

With his brother looking on behind him, a novice monk reads a religious text at the Thayanbu Temple in Bagan, Myanmar.

He shoots landscapes on occasion, but it’s the portraiture — the human subjects — that intrigue him the most.

“Landscapes just sit there, and all you have to do is wait for the right time of day, and, if you get lucky, you might have some weather with it,” he says. “But people? Just a minute change in facial expression changes the entire meaning of the photograph. I think any of my landscape photography would be more interesting if I put a person in it.”

But it’s not all about the craft itself. It’s also an excuse to push his own boundaries, to go a step further, to explore his wanderlust. When his travels began in earnest roughly 15 years ago, sparked by a photography tour of Egypt, he couldn’t have imagined where the camera would take him. Around the globe, of course, but inside out, as well.

“I’ve gone through some very emotional experiences with photography,” he says, “and I don’t think I ever would have been there without a camera in my hand.”

In a flash he’s back in Ethiopia’s remote Omo Valley, taking pictures at an orphanage built as a refuge from Mingi, the ritualistic killing of infants and children considered cursed by their tribes.

He’s in Vietnam, interviewing survivors of the My Lai Massacre.

He’s in Cambodia, shadowing a member of the genocidal Khmer Rouge.

He’s back at the Rohingya refugee camp near Cox’s Bazar on the southeast coast of Bangladesh. He’s here to collaborate with documentary filmmaker Lauren Anders Brown on a project for the United Nations Population Fund, but today he’s on his own. He’s sitting on the dirt floor of a small hut listening to a young woman tell her story. She’s wearing a hijab. Half her face is covered in scar tissue. Her name is Momatz, she says, already crying, and before she fled to Bangladesh, she lived in a small village in Myanmar with her husband and two young daughters. Everything changed the day the soldiers arrived. In the midst of a genocidal campaign against the Muslim Rohingya, the Myanmar Army marched every adult male to the center of the village and shot them in the chest. When her husband — still breathing — begged for water, a soldier cut his throat, she told Wallace, then turned to Momatz and the crying baby in her arms.

They threw her baby in a pile of burning debris, marched her and the other women to the only building not already on fire. They raped them all, locked the doors and let the house burn. Unlike so many others, Momatz was able to escape, though 30 to 40 percent of her body is now covered in scar tissue. Her other daughter, just 8 years old, survived, too. She’s sitting quietly in the corner of the hut, listening to her mother replay the nightmare.

“She tells this story to me, and I just feel like I’m hit by a shockwave,” Wallace says. “I couldn’t think. I couldn’t react emotionally. It wasn’t until later that night I digested what I heard.”

Still, he managed to get the shot: the worry in her brow, the horror reflected in her watery brown eyes.

A Rohingya woman named Momatz, burned during a genocidal raid on her village by the Myanmar Army, tells her story at a refugee camp in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh.

“You can just tell from Steve’s work that he has the consent of the people that are in his photographs: the way they look at the lens, their comfort level, their position and poise in that sense,” Anders Brown says. “I think that’s the doctor in him. It’s that medical ethic of do no harm.”

Steve Wallace is most at home in the third-world surrounds of parts of Southeast Asia, interacting with the people. “I feel that is where I should be,” he says. “Photography is the vehicle I use to experience the life of others.”

Which isn’t to say he never bends the rules. For a photograph that later won him first place in a contest hosted by Photo District News, a monthly trade publication for professional photographers, Wallace encouraged a group of novice monks — volunteers from a local monastic school — to run and play at the Hsinbyume Pagoda in Mingun, a small village in Myanmar. Yet another example of his mastery of light and color, the monks’ burgundy robes shout out against the chalk-white terraces of the pagoda and the feathered clouds above. It’s a singularly joyous photo: With big smiles and their arms raised high, the monks seem — if only for a moment — to be unleashed from all expectation. To be their boyish selves.

And yet, when Wallace returned several years later, his fixer told him their headmasters had seen the photos and they disapproved. Once the children have donned the robes, they said, they are representing the Buddha.

“You can see by the joy on their faces — when you get them away from their headmaster and allow them to do this — how happy they are,” he says. “Do I feel bad about allowing them to run and act like children? No. I don’t.”

He’s been called a travel journalist, a travel photographer, a photojournalist. None of them quite seems to fit, and at 66, he doesn’t really care. For Wallace, it’s all about the experience. The beauty. The laughing monks and the camels’ long shadows and that one cool morning in the warmest valley in Ethiopia, the Arbore tribe emerging from their huts at sunrise. It’s about Momatz and that nagging feeling he has a little more to give.

“I can’t say it’s going to change the world or anything like that,” he says. “But I feel like I’m helping out a bit.”

To read more articles like this, become a Mizzou Alumni Association member and receive MIZZOU magazine in your mailbox. Click here to join.

- Novice Monks walking through field with hot air balloons lifting off, 2018.

- Tonle Sap Lake, Cambodia, 2011.

- Gelada Baboon, Simian Mountains, Simian National Park, Ethiopia, 2020.

- Desert near Aswan, Egypt, 2009

- Swiss Guard, Vatican, Italy, 2014.

- Rice Terrances, Dazhai, China, 2019.

- Merchant, Chengkan Village, China, 2019.

- Member of the Miao Ethnic Group, the only group to own guns legally in China, Village of Basha, China, 2019.

- Horseman, Island of Java, 2018.

- Balinese Dancer, Indonesia, 2018.

- Rice Fields near Dien Bien Phu, Vietnam, 2015.

- Ethiopian Orthodox Priest, Lalibela, Ethiopia, 2020.